Social Engineering That Targets Senior Officials in 2025?

Social Engineering That Targets Senior Officials in 2025?

Senior officials sit at the crossroads of authority and access, making them high-value targets for cybercriminals. Unlike broad attacks that cast a wide net, the techniques aimed at executives are precise, sophisticated, and designed to bypass even the most advanced technical defenses.

This growing trend has placed methods such as whaling, spear phishing, pretexting, and impersonation at the center of modern cybersecurity concerns.

At its core, social engineering doesn’t exploit software vulnerabilities; it manipulates human behavior. Senior officials, with their ability to authorize financial transactions, access strategic plans, and influence entire organizations, represent an attractive gateway for attackers. A single compromised email or misplaced trust can open the door to data breaches, fraud, and reputational damage that ripple across industries.

This article examines the tactics most commonly used against senior executives, why these individuals are targeted, and how organizations can strengthen their defenses. By exploring both the human and technological aspects of these threats, we can better understand how to shield leadership from the growing wave of social engineering campaigns.

Start a Life-Changing Career in Cybersecurity Today

Why Senior Officials Are Prime Targets for Social Engineering

Targeting senior officials is not accidental; it is strategic. Executives and high-ranking leaders hold decision-making authority that directly impacts an organization’s finances, data security, and reputation. For attackers, compromising these individuals offers a shortcut to sensitive systems and high-value transactions without needing to break through multiple layers of technical defenses.

Unlike entry-level employees, senior officials often have fewer restrictions on their accounts, broader access to confidential information, and the autonomy to approve payments or sign off on strategic deals. This combination of authority and access makes them ideal candidates for exploitation. For instance, a well-executed whaling attack can trick a CFO into wiring millions to a fraudulent account or approving a contract embedded with malicious clauses.

Another factor is human psychology. Senior leaders are accustomed to urgency, delegation, and trust-based communication. Attackers exploit this environment by sending messages that appear urgent, authoritative, or tied to ongoing projects. The familiarity of the language lowers suspicion, increasing the likelihood of a quick response. In high-pressure settings, even a brief lapse in judgment can result in devastating consequences.

RELATED: Cybersecurity Internship Technical Interview Questions

What Are Social Engineering Attacks?

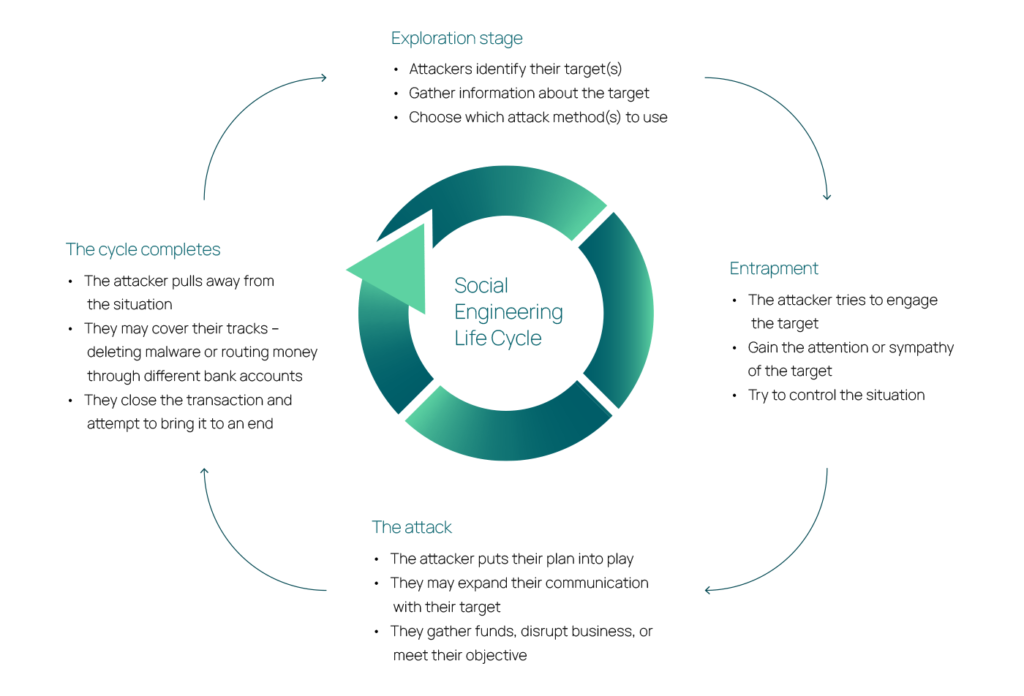

Social engineering is the art of exploiting human psychology to bypass technical safeguards. Instead of breaking through firewalls or cracking encryption, attackers rely on deception, persuasion, and manipulation to convince individuals to reveal information or perform risky actions. For senior officials, the stakes are particularly high because their roles naturally involve trust, authority, and access to critical systems.

These attacks are effective because they feel personal. Cybercriminals often research their targets in advance, using social media, company websites, and even press releases to understand an executive’s routines, contacts, and responsibilities. Armed with this information, attackers craft messages that appear authentic and relevant, lowering suspicion. A simple request for “urgent approval” or a call from a supposed business partner can be enough to trigger action.

Common objectives of social engineering campaigns include harvesting login credentials, gaining access to confidential documents, initiating fraudulent financial transactions, or planting malware within a corporate network.

Because the interaction feels legitimate, these attacks can succeed where automated security measures fail. In fact, a significant portion of modern data breaches begin not with technology, but with a carefully crafted email, phone call, or in-person interaction designed to trick a human being.

For senior officials, recognizing these tactics is not optional; it is essential. Understanding the psychology behind social engineering is the first step in building resilience against it.

Types of Social Engineering Attacks Targeting Senior Officials

Cybercriminals use a range of social engineering techniques, but when the target is a senior executive, the attacks are more tailored, polished, and persistent. Each method exploits authority and trust differently, making it crucial to understand how they work.

Whaling

Whaling is a specialized form of phishing that focuses exclusively on high-profile individuals such as CEOs, CFOs, and board members. These attacks are carefully personalized, often referencing real projects, partnerships, or industry events to appear credible. A single successful whaling attempt can result in fraudulent transfers, unauthorized access, or leaked corporate strategies.

Spear Phishing vs. General Phishing

While general phishing sends mass emails hoping a few recipients will fall victim, spear phishing, and especially whaling, are hyper-targeted. They incorporate personal details about the executive, such as recent travel, board meetings, or partnerships, making them far more convincing than generic scams.

Pretexting and Baiting

Pretexting involves inventing a believable scenario to justify a request. An attacker might pose as a legal advisor, auditor, or even another executive to request sensitive information. Baiting, on the other hand, tempts the target with something of value, like exclusive documents or “urgent” financial updates, that hide malicious intent.

Impersonation and Identity Fraud

Attackers may impersonate trusted colleagues, external partners, or government officials to gain credibility. With access to public data and digital tools, fraudsters can convincingly replicate writing styles, email formats, and even voices, further blurring the line between real and fake interactions.

Each of these methods underscores a critical reality: senior officials are not attacked at random. They are deliberately chosen, with strategies tailored to their roles, responsibilities, and influence.

READ ALSO: What Is Third-Party Vendor Risk Management (TPRM)? Complete Guide

The Significance of Targeting Senior Officials

When cybercriminals aim their efforts at senior officials, they are pursuing maximum impact with minimal effort. Unlike lower-level employees, executives sit at the center of decision-making and control over financial, strategic, and operational resources. A single compromised official can unintentionally unlock access that would take months, or even years, for attackers to achieve through other means.

The stakes are enormous. Senior leaders often have the authority to approve large wire transfers, greenlight acquisitions, or share confidential business intelligence with external stakeholders. For attackers, convincing one individual to click a link or authorize a transaction can result in multi-million-dollar losses, intellectual property theft, or long-term access to an organization’s systems.

Equally significant is the ripple effect. When an executive is compromised, the trust dynamic within the organization shifts. Employees are more likely to comply with fraudulent instructions if they believe they originate from the top. This makes the fallout not just a matter of financial loss but of organizational integrity, as attackers exploit the credibility attached to a leader’s name and position.

For companies, the damage extends beyond immediate costs. A successful attack on a senior official can erode shareholder confidence, weaken customer trust, and draw scrutiny from regulators. In extreme cases, it can even end careers, as seen in high-profile breaches where executives were forced to resign following security lapses.

The focus on senior officials is therefore not incidental; it is a calculated strategy by cybercriminals to strike at the very heart of organizational power.

What Is a Whaling Attack?

Among the many forms of social engineering, whaling stands out as one of the most dangerous because it is designed specifically to target senior officials. The term reflects its intent: instead of going after “small fish” with mass phishing campaigns, attackers go after the “big fish”, high-level executives whose decisions can move millions of dollars and alter corporate strategy.

A whaling attack typically begins with a message that appears highly credible. The email or phone call is not generic; it is crafted with details pulled from press releases, social media, and professional networks. Attackers may reference a recent acquisition, a board meeting, or even an executive’s travel schedule to make the request believable. The goal is to bypass suspicion by making the communication feel routine and relevant.

These attacks employ both technological and psychological tactics. Spoofed email domains or lookalike websites are used to trick recipients into believing they are interacting with trusted contacts. At the same time, the message often conveys urgency or authority, two psychological triggers that pressure executives to act quickly without full verification. A request to “approve funds immediately” or “share confidential documents before a deadline” exploits the fast-paced environment in which leaders operate.

The intended outcome is usually a secondary action: transferring funds to a fraudulent account, disclosing credentials, or clicking on a malicious link that installs malware. In some cases, attackers follow up with phone calls to reinforce the illusion of legitimacy, further lowering the victim’s guard.

What makes whaling so effective is not just the sophistication of the deception but the value of the target. A single successful attempt can yield more than hundreds of generic phishing emails combined, making it a preferred method for cybercriminals who seek high returns with precision.

SEE MORE: What Is Enterprise Risk Management (ERM)? Types, Pillars, Stakeholders

Social Engineering: Real-World Consequences

The risks associated with social engineering are not theoretical; they translate into measurable financial, operational, and reputational damage. When senior officials are deceived, the effects are amplified across the entire organization, often with long-lasting consequences.

Financial Impact

Whaling and related attacks frequently lead to substantial monetary losses. Fraudulent wire transfers can siphon millions in a single incident, while the costs of remediation—legal fees, regulatory fines, and system overhauls—can multiply the damage. According to the FBI, Business Email Compromise (BEC), a crime category that includes executive-targeted phishing, has resulted in more than $55 billion in global losses over the last decade.

Data and Privacy Breaches

Beyond direct financial theft, attackers often use these tactics to install malware or steal sensitive information. Breaches involving trade secrets, customer data, or intellectual property can cripple competitive advantage. With regulations such as GDPR and NDPR imposing strict penalties for data mishandling, the exposure of confidential data can carry both legal and financial consequences.

Reputational Damage

Perhaps the most enduring consequence is reputational harm. Customers, shareholders, and business partners may lose confidence in an organization’s ability to safeguard its operations. For senior officials themselves, falling victim to a whaling attack can be career-defining, eroding credibility and, in some cases, resulting in dismissal. The case of Austrian aerospace company FACC, which lost €50 million in a whaling scheme and subsequently fired its CEO, illustrates the far-reaching impact on leadership accountability.

In short, the consequences of social engineering attacks against executives extend far beyond immediate financial loss. They weaken organizational trust, attract regulatory scrutiny, and can permanently tarnish the reputations of both companies and the individuals who lead them.

What Type of Social Engineering Targets Senior Officials? Threats and Tactics

Social engineering tactics evolve continuously, and attacks on senior officials are no exception. Cybercriminals are refining their methods to exploit both digital and human vulnerabilities, making it harder for traditional defenses to keep up. Understanding the current threat landscape is essential for anticipating how these schemes are carried out.

Supply Chain Exploitation

One emerging tactic involves infiltrating or impersonating trusted suppliers and partners. Since executives frequently handle vendor contracts and payments, fraudulent requests disguised as routine supplier communications can slip past suspicion. By exploiting established trust in supply chains, attackers increase their chances of success.

Blending Digital and Traditional Fraud

Today’s social engineering attacks often combine online deception with offline tactics. An executive might receive a spoofed email requesting urgent action, followed by a phone call to “confirm” the request. This layered approach makes the attack feel authentic, leveraging the psychological weight of verbal reassurance.

Increased Personalization

With the abundance of publicly available information, attackers can create highly detailed and convincing profiles of their targets. Details about travel, conferences, partnerships, or even hobbies shared on social media are weaponized to craft messages that feel tailored. A request referencing a recent board presentation or a charity involvement can disarm skepticism more effectively than a generic phishing attempt.

The Role of Social Media

Social media has become a double-edged sword for executives. While it is an essential tool for visibility and communication, it also provides adversaries with valuable insights. Personal and professional updates can be pieced together into a playbook for exploitation. Studies have shown that phishing campaigns using social media context are significantly more successful than those without personalization, underscoring how dangerous oversharing can be.

The sophistication of these tactics highlights a troubling reality: senior officials are now facing threats that blend technology, psychology, and even real-world social engineering. Defenses must therefore evolve to match the creativity and persistence of attackers.

READ: How to Become a GRC Analyst?

Fortifying Defenses Against Social Engineering

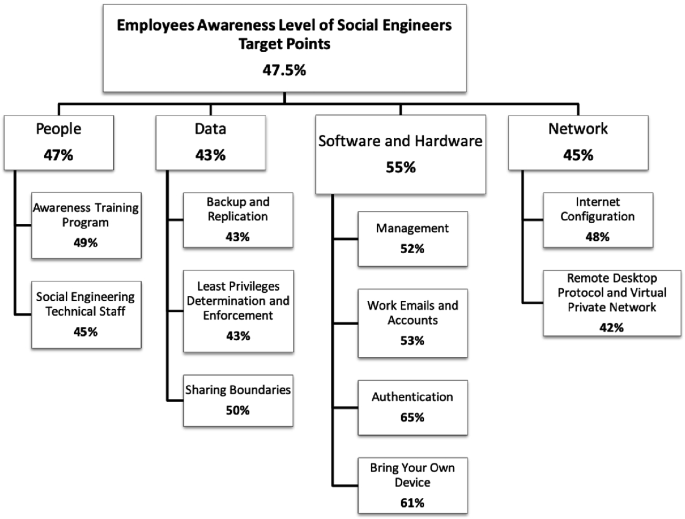

Defending senior officials from social engineering requires more than technical safeguards—it demands a layered approach that combines culture, training, technology, and well-defined procedures. Because these attacks exploit human behavior, organizations must strengthen both their systems and their people.

Cultural and Educational Strategies

Awareness is the first line of defense. Executives and employees alike should receive regular training that highlights how attacks like whaling or pretexting unfold. Simulated phishing exercises, real-world case studies, and continuous refreshers ensure that awareness doesn’t fade over time. Beyond formal training, fostering a culture where employees feel comfortable questioning unusual requests—even from leadership—reduces the stigma of “second-guessing” authority.

Technical Safeguards

Advanced email filtering, domain authentication, and anti-phishing tools can reduce the number of malicious messages that reach executives. Incorporating artificial intelligence and machine learning helps detect unusual patterns of communication, such as unexpected requests for large transactions. Strong authentication protocols, like multi-factor authentication (MFA), add an extra layer of protection even if credentials are compromised.

Operational and Procedural Measures

Well-defined processes are critical. High-value actions—such as approving payments, sharing sensitive data, or authorizing contracts—should never rest on a single individual’s approval. Dual verification protocols, call-back confirmations, and in-person validations create barriers that prevent attackers from exploiting urgency. Just as important is a tested incident response plan, ensuring organizations can respond quickly and effectively if an executive is targeted.

Empowering the Human Factor

Ultimately, social engineering succeeds because it exploits human psychology. Training leaders to pause, verify, and challenge suspicious requests can be just as effective as deploying new technology. Encouraging executives to treat unexpected messages with skepticism, no matter how legitimate they appear, creates resilience at the highest levels of decision-making.

Conclusion

Protecting senior officials from social engineering requires recognizing that authority and access are a double-edged sword. The very qualities that make executives effective leaders also make them attractive targets. Cybercriminals exploit urgency, trust, and influence to bypass traditional defenses, making whaling and other targeted schemes among the most damaging forms of attack today.

A strong defense begins with awareness. Training programs tailored for executives, reinforced by a culture that encourages verification over blind trust, can drastically reduce vulnerability. Complementing this human-focused approach with advanced technical safeguards, such as AI-driven detection, multi-factor authentication, and robust verification protocols, ensures that organizations are not relying on a single layer of protection.

The stakes are high: financial losses, regulatory penalties, and reputational harm can all result from a single lapse in judgment. But by adopting a multi-faceted strategy that blends people, processes, and technology, organizations can significantly limit the risks. In the battle against social engineering, resilience is not built overnight, it is cultivated through continuous vigilance, executive buy-in, and a commitment to treating cybersecurity as a shared responsibility.

For today’s leaders, the message is clear: understanding how and why social engineering targets senior officials is no longer optional. It is a necessary step in safeguarding both personal credibility and organizational integrity in an increasingly deceptive digital landscape.

FAQ

What is a Tailgating Attack?

A tailgating attack occurs when an unauthorized individual gains physical access to a restricted area by closely following an authorized person. For example, an attacker might slip in behind an employee entering with a valid key card.

Because the intruder relies on exploiting human courtesy, such as someone holding the door open, the tactic bypasses security systems entirely. Tailgating underscores the fact that cybersecurity is not just digital; it also involves controlling physical access to sensitive environments.

What are Cookies?

Cookies are small text files stored on a user’s device by websites they visit. They serve several purposes: remembering login details, personalizing browsing experiences, and tracking user behavior for analytics or advertising. While cookies are essential for functionality, they can also raise privacy concerns if misused, as they provide insights into browsing patterns that malicious actors could exploit.

What is the Difference Between Piggybacking and Tailgating?

Both piggybacking and tailgating involve unauthorized entry into a secured space, but the key difference lies in awareness. In tailgating, the authorized individual is unaware that someone has slipped in behind them.

In piggybacking, the authorized person knowingly allows the intruder inside, often because they are deceived into believing the person has legitimate access (e.g., someone pretending to be a new employee who forgot their badge).

What is the CIA Triad?

The CIA triad is a foundational model in cybersecurity that outlines three core principles of information security: Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability.

Confidentiality ensures that sensitive information is only accessible to authorized users.

Integrity guarantees that data remains accurate, consistent, and unaltered by unauthorized actors.

Availability makes sure that systems and data are accessible when needed, preventing disruptions to business operations.

Together, these principles guide the design and implementation of security policies and controls across organizations.